Every time I scroll through the latest news on the upcoming presidential elections and see Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk in action, I get this strange sense of déjà vu. It’s like I’ve seen this show before. Probably takes me back to the early days of my journalism career in Russia, where I watched Vladimir Putin dismantle independent media right before my eyes. And he didn’t even have to get his hands dirty—the oligarchs did the heavy lifting for him. But let’s be clear, Russian oligarchs, they were not like Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos… oh wait, they were exactly like Musk and Bezos. Young and ambitious, they believed they could control the country and use an authoritarian president to serve their interests.

Obviously it’s a story about Russia, how democracy dies in silence - and maybe not only about Russia.

I remember the year 2000 like it was yesterday, when Putin was elected president for the first time. Back then, I was just a journalism student already working as a reporter for a popular online newspaper. None of my professors believed anything would really change after the election. In the ’90s, Russian media was incredibly free-spirited: they boldly criticized the government, exposed corruption, and didn’t hold back with the harshest words for officials. They openly wrote that President Yeltsin was old, physically incapable of governing, and that his family was mired in corruption and dependent on oligarchs. It was all true. And it seemed that things would stay the same under Putin.

“Look, if Putin intended to take freedom of speech seriously, he’d have done something about it by now—especially during this campaign season, when media criticism could harm him the most,” my professor, a major newspaper editor, would say. His newspaper, actually, supported Putin.

Media independence back then was largely secured by the fact that all the TV channels, newspapers, magazines, and radio stations were in private hands. Although, to be fair, almost all Russian media belonged to oligarchs. They were just another asset in the collection, alongside banks, oil companies, or metallurgical plants. And for a few, like Boris Berezovsky and Vladimir Gusinsky, the media was a tool for political influence—something they bought on purpose, with the goal of gaining power.

“Nothing can change,” my older journalist colleagues reassured me (though mostly they were reassuring themselves). “People have gotten used to freedom of speech; it’s impossible to take it away now. Putin won’t be able to bring back Soviet-style censorship, even if he wanted to.”

So, what happened next? Why was it that, just four years later, by the end of Putin’s first presidential term, independent media in Russia had nearly vanished?

Putin didn’t pass any draconian laws, shut down any newsrooms, throw journalists in jail, or have anyone killed. The media laws remained as liberal as ever, and censorship was still banned by the constitution.

It was simply that Putin got a little help from his oligarch friends.

Take Roman Abramovich, for instance—he bought “Channel One” from Boris Berezovsky, just as Berezovsky had begun criticizing Putin’s handling of the Kursk submarine disaster.

Then there was NTV, another opposition channel, which ended up in the hands of a new owner, Gazprom. The journalists tried to resist, protested, even considered quitting. But eventually, half of them decided to stay—especially once the new owner offered them rather appealing terms.

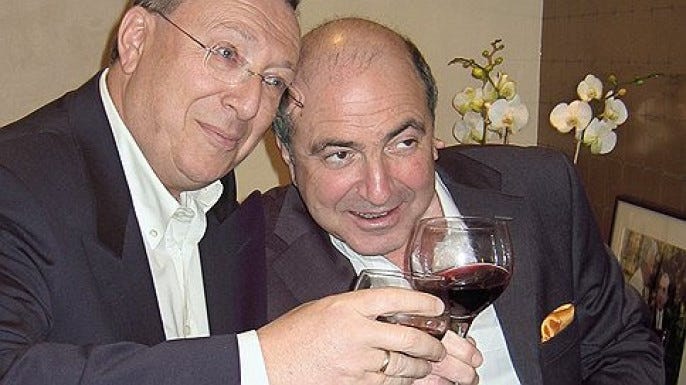

Gusinsky and Berezovsky

In 2001, I landed a job at Kommersant—one of Russia’s most respected newspapers, kind of like The Washington Post. Back then, it was owned by Boris Berezovsky. He had supported Putin before the election, but once Putin became president, Berezovsky went into opposition and moved to London.

Thanks to this twist, Kommersant managed to stay one of the last truly independent media outlets in Russia for a while. The editor-in-chief, Andrey Vasiliev, worked hard to keep it that way. When he got calls from the Kremlin, he’d typically respond, “I’d love to help, but if I do, Berezovsky will fire me immediately.” And when the oligarch himself called from London, Vasiliev would say, “You know, I’d gladly do whatever you want, but if I do, they’ll shut down the paper!” This balancing act kept Kommersant genuinely independent for quite some time.

It all ended in 2008 when another oligarch, Alisher Usmanov, loyal to Putin, bought the newspaper. The editorial policy changed immediately, and I soon resigned.

By the way, Alisher Usmanov was considered quite the respectable businessman back then; he had even bought shares in Facebook in 2009, becoming one of its early big investors.

Do I really need to name the other oligarchs who were complicit? All the major businessmen acted the same way, consistently choosing their own prosperity over freedom of speech.

In 2014, when we made another attempt and created the opposition TV channel Dozhd, it, too, was nearly destroyed in a rather sophisticated manner. They couldn’t buy us out—but Kremlin officials personally called up big businessmen who owned cable and satellite networks. They were given a choice: lose their other businesses or disconnect our channel. Naturally, everyone chose the former. Nothing personal, no politics, just business.

So many years have passed since then that many Russians have forgotten it could ever be any different. Meanwhile, Kremlin officials genuinely believe this is just the natural order of things: whoever pays calls the tune—that’s their cynical motto. Then again, it’s clear that this is a fairly international motto.