Putin and Assad

Interview with a Dictator

I met Bashar al-Assad in 2008. Back then, he wasn’t yet a global pariah, but he already sensed that his prospects were bleak. He never liked talking to journalists, but in September of that year, he suddenly became eager to give an interview to the Russian press. That “Russian press” turned out to be me, an international columnist for Kommersant, Russia’s leading independent newspaper.

Assad’s sudden desire to speak made sense—he was incredibly buoyed by the August war in Georgia. “If there were people in Russia who thought the U.S. could be a friend, I think there are no such people left now,” he told me with glee.

In essence, that interview could be summed up with a single thought: “Finally!” Assad had long hoped that Russia would stop pretending to be an democracy and would instead embrace being a typical tyranny—a normal rogue state. He wanted Russia to shed its inhibitions about selling missiles to his country, Syria, as well as to Iran. And after the war with Georgia, he seemed convinced that the Rubicon had been crossed, that there was no turning back, and that the West would never forgive Russia for that war.

“What’s happening to Russia now is what already happened to us: Georgia started this crisis, but the West blames Russia,” Assad fumed. “This process has been going on for years: first they wanted to surround Russia with a ring of hostile governments. This is the apex of their attempts to surround and isolate Russia.”

Immediately after our interview, Assad flew to Sochi for a meeting with Russia’s president, Dmitry Medvedev. Clearly, he repeated the same arguments there—but he chose the wrong audience. Or rather, he was premature. Not only did Medvedev fail to strike any deals with Assad, but two years later, he voted alongside the Americans at the UN to impose sanctions against Iran and then supported the operation against Libya—the very one Putin would later call a “crusade.”

In 10 years Russian foreign policy traveled an astonishing path. If, in 2008, Bashar al-Assad’s words seemed like paranoid delusions, by 2018, they had become mainstream foreign policy.

Our Son of a Bitch

During the Soviet years, the Middle East was always considered Moscow's zone of special interest. No other region received as much attention from Soviet central television's international correspondents. No foreign leader (outside the socialist bloc) visited the USSR as often as the head of the Palestine Liberation Organization, Yasser Arafat. And no country (including the U.S.) was vilified by Soviet propaganda as fiercely as the "Israeli military machine."

If the Middle East was the Soviet Union's "backyard," this approach was abandoned almost overnight with the USSR’s collapse. The new Russian state immediately established relations with Israel, which were eagerly developed thanks to the efforts of the emerging Jewish oligarchs.

Putin never took the Arab states seriously. He personally delved into some international affairs, but never the Arab world. In essence, the Arab East was left to adventurers. Shady deals were made there, having little to do with politics—after all, corruption in the Arab states was always at least as rampant as in Russia.

Everything changed with the Arab Spring. Vladimir Putin viewed the uprisings against Hosni Mubarak and Muammar Gaddafi in 2011 as if he had seen himself in them. What happened next with Bashar al-Assad struck an even deeper nerve.

Assad’s main difference from his Arab dictator neighbors lies in his panic-stricken fear of a color revolution. In 2011, the Arab Spring erupted—mass protests toppled leaders in Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt. Assad, however, resolved to resist at any cost.

The unrest, despite the government’s harsh measures, did not subside. Instead, it escalated into a civil war. Assad stubbornly waged this war, regardless of the casualties—5,000 lives were lost in the first year alone. Bashar al-Assad’s example demonstrates that blind, relentless struggle to cling to power—no matter the cost—can sometimes be effective. The absence of any coherent plan or strategy is, in itself, a strategy.

Vladimir Putin often recalls a phrase attributed to U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt, supposedly said about the Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza: “He may be a son of a bitch, but he’s our son of a bitch.” Putin frequently uses this quote as a glaring example of American double standards. Given that Putin perceives all foreign policy exclusively through the lens of his own experience—as a rehearsal of American plans to remove him from power—Bashar al-Assad became his “son of a bitch.”

Here is how one of Putin’s close advisors described the president’s reasoning regarding events in Syria: Bashar al-Assad was an ordinary Arab leader. No worse, no better than the others. He was roughly the same as the kings of Saudi Arabia, Morocco, or Jordan, or the presidents of the UAE, Sudan, or Algeria. Why did the West have no complaints about some but harshly criticized others? Why was Saudi Arabia allowed to publicly hang and behead people without being reproached for human rights violations, while Syria was condemned for far less severity? The explanation, Putin reasoned, was simple: it’s because Syria was Russia’s ally. It was the only country where Russia still maintained a military base. It was a regime that was buying Russian weapons and asked for Russian help.

The fact that Assad used weapons against his own civilian population was interpreted by Putin in his own way: Assad was the first to successfully resist the Arab Spring. Putin recalled that ten years earlier, in 2004 and 2005, a wave of color revolutions had begun across the former USSR. The first to dare open fire on hundreds of protesters was Uzbekistan’s president, Islam Karimov. Putin immediately supported him and promised military assistance next time—what mattered most was that Karimov stopped the chain reaction.

When Syria’s civil war began in 2011, Putin experienced a sense of déjà vu. Once again, he was under threat, and once again, he had an eastern dictator to thank for his obstinacy—this time, Bashar al-Assad, who halted the Arab Spring. To Putin, the Arab Spring was a dress rehearsal for revolution in Russia, and Bashar al-Assad effectively shielded Russia from the American plot.

Ticket to the World

However, Syria truly became significant for Putin only after Russia annexed Crimea and began its military intervention in Donbas. In June 2014, the downing of the Malaysian airliner over the Donetsk region turned Russia into a pariah state. Putin virtually stopped traveling for international visits—he wasn’t welcome any longer. At the 2015 G20 summit in Brisbane, Australia, he was placed on the far edge of the group photo, and no world leader sat at his table during the working breakfast. Seriously—he sat alone. Later, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov attended the Munich Security Conference, where the entire hall laughed at him as he desperately tried to deny that Russia was sponsoring the militants attacking Eastern Ukraine.

By 2015, Putin found himself in a deeply uncomfortable position, no longer feeling like a respected world leader. He had lost his voice on all major international issues—whether it was Iran, the Middle East, European security, or any other topic. This was precisely what he had sought most since the beginning of his presidency, regularly advocating for a new Yalta Conference. The old world order had collapsed, he argued, and it needed to be replaced with a new one.

This is where Bashar al-Assad came into play. He became Putin’s new ticket back into the world of big politics. The beginning of Russia’s operation in Syria brought Moscow back to the Middle East and into the club of serious world leaders.

In the fall of 2015, Putin traveled to the UN and delivered a speech proposing the creation of a new international coalition, which, in his words, would serve as a continuation of the anti-Hitler coalition of the 1940s. This time, he meant that all the world’s nations should unite against ISIS.

His idea sounded rather bizarre, and no one took it seriously—after all, how could there be a coalition with a man who had just sanctioned an attack on a neighboring country and annexed part of its territory? But Putin was no longer fazed by this. He wasn’t expecting a serious discussion of his fantastical idea. Instead, he launched his own operation in Syria, whose real goal, of course, was not fighting ISIS but keeping Bashar al-Assad in power. Russian forces began bombing not the positions of the Islamists but those of the opposition to the Syrian regime.

Participation in the Syrian war earned Putin precisely the image he wanted—that of a global villain. It didn’t matter that he was now seen as a villain; what mattered was that he had become a key player again. The flood of Syrian refugees pouring into Europe was very good news for him. It meant that European security was in his hands. Once again, he could influence how European politicians felt. Once again, he had become a crucial partner at the negotiating table.

When Western media wrote with horror about the Russian bombings of Aleppo, comparing them to the monstrous destruction of Grozny in the 1990s, for Putin, this wasn’t some dreadful news — it simply reaffirmed his significant international status.

All About the Money

At the same time, the Syrian war was used by Russian military officials much like previous military operations — as an opportunity for personal enrichment. For example, in 2017, a curious incident occurred. Russia’s Chief Military Prosecutor, Sergey Fridinsky, was scheduled to deliver his annual report to the upper chamber of the Russian Parliament — the Federation Council. The report had already been circulated to senators the day before, revealing how much money Russia was spending on the Syrian operation and how dramatically the military budget had truly grown. For any unprepared reader, it was obvious that the funds were being embezzled.

However, the report never happened because, on the day Fridinsky was supposed to speak, he submitted his resignation and retired. The copies of the report, which had already been distributed to senators, were collected back. It never became public knowledge. Ultimately, embezzling the military budget to the benefit of generals has never been condemned by Vladimir Putin. It is simply part of the rules of the game.

Another critical chapter in Putin’s Syrian venture was the emergence and meteoric rise of Wagner PMC. It was in Syria that Yevgeny Prigozhin first saw himself as a warlord and became a noticeable political figure and business entity. Syria is where his private military company earned its first millions and proved it could be far more effective than Russia’s regular army. It was also in Syria that his rivalry with Defense Minister Sergey Shoigu began.

The defining moment in this conflict was February 2018 — the infamous battle at Conoco Fields. Wagner fighters approached dangerously close to positions held by American troops guarding an oil processing plant in Khasham. At the time, the U.S. military contacted the Russian Ministry of Defense to inquire about the identity of these armed individuals. The Russian military disavowed them. Shortly after, around 300 Wagner fighters were killed. In essence, this became the first direct battle involving American and Russian combatants in history. Even during the Cold War, Soviet and U.S. soldiers had never fought directly. The Kremlin remains convinced that this military operation was only possible with the personal approval of Donald Trump. That moment fundamentally changed Putin’s attitude toward Trump.

However, beginning in 2022, after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Syria’s importance diminished somewhat. Putin had already fully solidified his image as the world’s leading villain. Moreover, Russia no longer had the resources to supply weapons and troops to Syria. All available forces were focused exclusively on Ukraine. As a result, Bashar al-Assad became a secondary client of Putin’s.

Ironically, the attack on Ukraine was inspired by television images that Putin had seen — the Taliban taking Kabul after U.S. troops had withdrawn. Now Putin finds himself in the same situation. He is forced to watch on television as the Syrian opposition takes Damascus.

Not-So-Soviet Union

Over the past few years, Putin has repeatedly speculated that he is reviving the Soviet empire and would never repeat the mistakes made by Mikhail Gorbachev.

As is well known, in 1989, Gorbachev withdrew Soviet troops from Afghanistan after a decade-long, protracted military adventure. Simultaneously, he put an end to the so-called Brezhnev Doctrine — the Soviet foreign policy system that mandated intervention in the internal affairs of any Eastern Bloc country if it dared pursue political reforms or changes not coordinated with Moscow. In 1989, Gorbachev announced to all his Eastern neighbors that they were no longer required to run every step past him.

What immediately followed was the total collapse of the old system in Eastern Europe. Within months, the Berlin Wall fell, Poland’s Solidarity movement took power, Czechoslovakia’s communist government resigned, and dissident Václav Havel became president. Finally, Romania’s totalitarian dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu was executed. These are precisely the mistakes Putin constantly refers to and promises not to repeat.

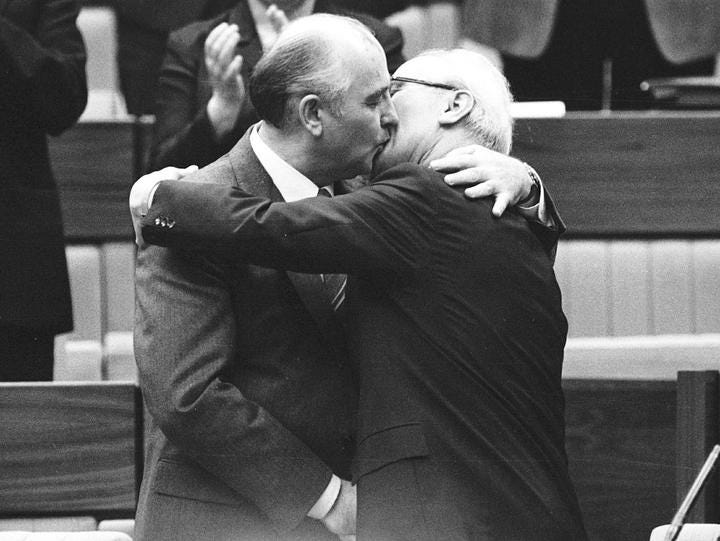

Mikhail Gorbachev and GDR leader Erich Honecker

At the same time, it’s no secret that Gorbachev made those decisions not because of some idealistic, deliberate vision. No, he was certainly enchanted by the idea of liberal freedoms and human rights, but, first and foremost, his approach was pragmatic and forced. The Soviet economy could no longer sustain the unbearable burden taken on by Brezhnev’s Politburo. Two-thirds of the Soviet economy was devoted to servicing the military-industrial complex. There simply wasn’t any strength left.

The current Russian economy bears a striking resemblance. It has been entirely reoriented to serve the military-industrial complex. Everything done within the Russian economy is aimed at being useful and essential to the war against Ukraine. In essence, Putin has restored Brezhnev’s model of governance, albeit with a twist: this is still not a planned economy but an extreme form of capitalism. Nevertheless, it is increasingly morphing into a system of state capitalism, centrally controlled.

However, it is already clear that the Russian economy lacks the resources to sustain anything resembling a Soviet empire. Moreover, Russia cannot even afford to manage two wars simultaneously, whereas in the 1980s, the Soviet Union financed not just the war in Afghanistan but also propped up puppet regimes in Angola, Ethiopia, North Korea, Cuba, and bankrolled all the Warsaw Pact countries.

The fact that Putin abandoned Bashar al-Assad speaks volumes. First, part of the explanation lies in the far more chaotic nature of governance today compared to Soviet times. There is no system in present-day Russia. It’s more of a chaotic scramble by various adventurers to cash in, slicing off pieces of the state budget.

The case of Yevgeny Prigozhin is a prime example. Nothing like Prigozhin could have existed in the Soviet Union. Assad’s downfall partly reflects that Moscow simply forgot and didn’t pay attention. The Syrian situation fell so far down the list of priorities that it slipped from their minds. This carelessness accurately mirrors the essence of Putin’s bureaucratic system.

However, there’s another reason Russia chose not to stand by Assad at all costs. Putin surely understands that his ultimate goal is not to create a colossal Soviet-style empire or maintain an extensive network of subsidiaries across the globe. As much as he might want this, he is forced to admit that it is physically impossible — he simply doesn’t have the money for it.

Moreover, the war in Ukraine was never about acquiring new territory. If anything, it is a war not for Ukraine, but for Russia. Its true purpose is to guarantee Putin's hold on personal power in his own country, not to expand its borders. In this sense, maintaining the Syrian regime at all costs no longer aligns with Putin’s objectives. On the contrary, Bashar al-Assad has already served his purpose, brought the required benefit, and has now been written off. Putin’s focus is solely on retaining his own grip on power.

For this, he has a remarkably reliable recipe: to prolong the war in Ukraine for as long as possible — ideally, forever. A state in a perpetual state of war is the most governable and best suited for authoritarian, dictatorial rule.